There was a lot of borrowing and sharing of material in the days of silent comedy shorts, a tradition that grew out of vaudeville and circus. In the milieu of live comedy performance, there were certain routines that were a particular comedian’s property, to be sure, but there were many routines that everyone knew and performed. We just know them by the silent comedy star who committed it to film.

The business Keaton does tipping his hat and shaking hands with someone at the beginning and end of Spite Marriage is the opening section of a very old circus routine called “Dead And Alive”. That routine also contains the bit where someone is lying down, unconscious, and one arm goes up. The second comic pushes it down, and the other arm goes up, and the comic pushes it down and one of the other comic’s knees goes up, and on and on. You’ve seen this in a few places, I’m sure.

There were a few gags in some of the Musty Suffer comedies that Steve Massa and I were surprised to see in a 1916 comedy, considering we’d known those gags only from later shorts by other silent clowns. These gags may have been part of the slapstick zeitgeist, but some seemed original and their turning up elsewhere could just be comedians’ minds working the same way. Did Ernie Kovacs see The Cameraman and The Play House somewhere when he was growing up in Trenton NJ before making his Baseball Film in 1951? Highly unlikely, and even more unlikely that he’d heard of “Slivers” Oakley’s vaudeville routine of a one-man baseball game (although Keaton must’ve known of or had probably seen it).

When we showed The Rough House (1917) during the Arbuckle retrospective that I co-organized with Ron Magliozzi and Steve in 2006, there was an audible gasp from the audience during the moment when Roscoe sticks forks in a pair of dinner buns and does the dance of the rolls from “The Gold Rush”, made about seven or eight years later (depending on when Charlie shot that scene).

Steve Massa, Rob Stone and I had a similar reaction to the opening sequence of Marcel Perez’s A Scrambled Honeymoon (1916) the first time we watched it, at the Library of Congress’ Packard Preservation Campus.

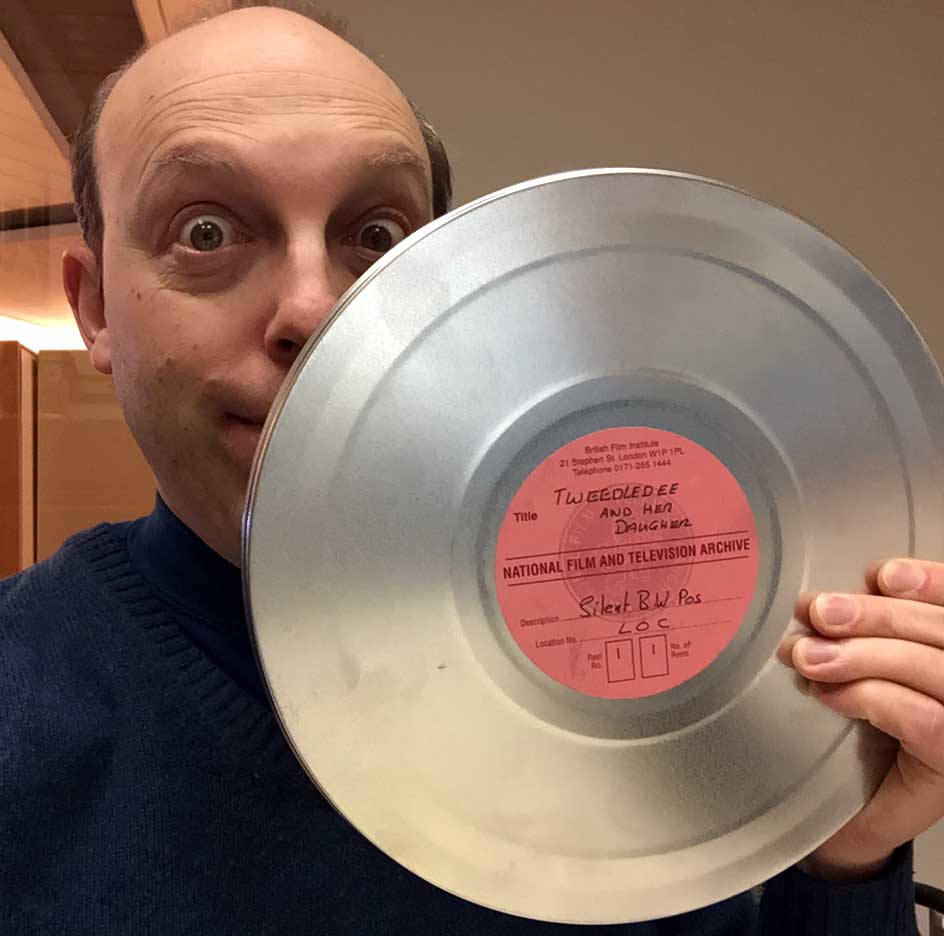

Tweedledee and Her Daughter is not a known Marcel Perez title, but Steve had a hunch it was a Perez film. It was one of several films the Library of Congress had acquired new prints of from the BFI (British Film Institute) a few years ago. Sometimes Nilde Barrachi was billed as Tweedledee, since Perez was known as Tweedledum. But why the title “Tweedledee and Her Daughter”? We found out as soon as the count-down leader ended and the film — or what survives of it — began.

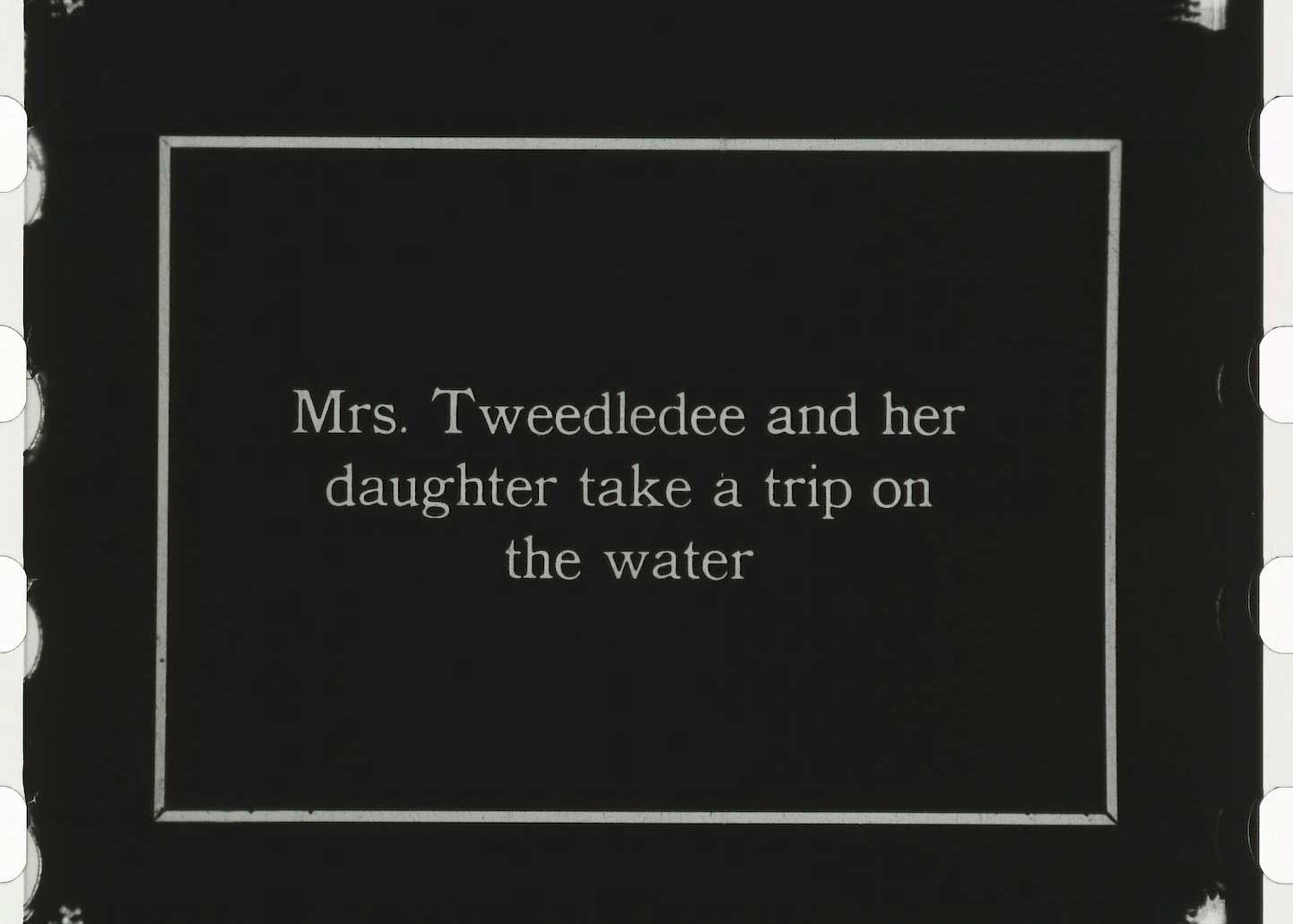

If you’ve attended Mostly Lost for any number of times, you’ve seen some unidentified or misidentified films listed in the screening program as having a certain main title, but before it hits the screen Rob Stone may announce to the crowd-sourcing brain trust in the theater that it may just be the first title on the reel. There seems to have been a cataloguing practice in a number of archives at one point of listing an unidentified film by the first title card on the reel, even if that title card was an intertitle. Sometimes eBay sellers do the same thing – I know I’ve won a couple of rare comedy shorts that were listed (and not bid on) by their first intertitle.

The first thing at the head of the print is an intertitle that says “Mrs. Tweedledee and her daughter take a trip on the water.”

Okay, mystery solved. Now to watch the reel of film, and see what the action is so Steve can match it up with a synopsis in the trades. And that’s when we had our “what the — ?” moment. The opening gag sequence is basically the routine Chaplin does in The Adventurer with him swimming to save a woman, sees a prettier and younger woman drowning nearby, and leaves the less attractive older woman to drown while he saves the pretty one. Only in this case Louise Carver and Nilde are in the parts Marta Golden and Edna play. And — the Perez comedy was shot in 1916, while The Adventurer was filmed in 1917.

Did Chaplin see what Steve shortly thereafter ID’ed as A Scrambled Honeymoon? Could be. It’s not a quick throwaway gag, as Arbuckle’s roll dance was. Perez really mines the situation for a number of developments that ultimately loop in some faux Keystone cops coming to poor Louise’s rescue (this was filmed for Eagle in Jacksonville, Florida). So it’s possible that, if Charlie did actually see Honeymoon somewhere, it might have made an impression on him. And, being the late ‘teens, the idea of “recycling” the routine was not necessarily out of the question. Larry Semon stole from himself many times throughout his career in short comedies.

The print is a single reel of around 900’, and turned out to be the first reel of a two-reeler that Perez made. Perhaps the second reel is not gone forever and is out there somewhere, either completely unidentified, or listed in an archive’s catalog by whatever the first intertitle of reel two is.

A Scrambled Honeymoon is on The Marcel Perez Collection: Volume 2, available on Amazon on February 27, 2018.

A Scrambled Honeymoon is seen on the Marcel Perez Collection: Volume 2 DVD in a 2K scan from a 35mm print in the collection of the Library of Congress. It was rendered at 20 fps, and some minor stabilization and clean-up was done on the scan. New opening titles were created based on the surviving ones from A Busy Night and A Bathtub Elopement, both of which are on the first Marcel Perez Collection DVD.