Buster Keaton said in interviews that one of the challenges of moving into feature-length was that you couldn’t do “impossible gags”. Everyone had to give this up when sound came in.

Keaton was referring to gags that didn’t have to be grounded in the story’s reality. The surreal, bizarro gags that we associate with silent comedy shorts. Sure, he snuck a few in here and there — like the location dissolve in Seven Chances — and got away with it one last time by making almost all of Sherlock Jr. a dream sequence. Although, because we expect these kinds of gags in silent movies, even when they continue into the second half of the film, when Keaton as Sherlock, Jr. dials the combination of a safe, opens its door, and exits out onto the street, as viewers we’re not necessarily thinking “oh, of course, this is part of Buster’s dream”. That moment doesn’t really happen for the audience until Buster sinking into the river dissolves into Buster in the projection booth.

This type of gag Keaton referred to as “impossible” brings us back to what I noticed about Chaplin in the employment office in A Dog’s Life. With Silent Film, as a gag writer or stunt coordinator you had the freedom to create gags and stunts that can’t happen in real life. Because reality grounds you with the laws of physics and gravity.

But Silent Film’s silence and speed-up, aided by the monochromic unreality, allowed creators in the 1910s and 1920s to think like cartoon gag writers and directors in the 1930s and 1940s did. What’s clear, to me anyway, from watching hundreds of silent comedies, as well as action pictures like Fairbanks features, westerns and serial episodes, is that the understanding everyone had was that you could come up with a gag, stunt, or piece of business that couldn’t be done in real life. And, by reverse-engineering it through choreography and/or adjusted movement, combined with a specific cranking speed and perhaps elements of stagecraft and sleight-of-hand, that gag could be made to exist.

Partnering with the physical and undercranked execution of these stunts and gags was what I referenced above as thinking like you’re making a 1940s cartoon at Warner Brothers. The expectation of reality with Silent Film is such that you don’t have to have much regard for logic, consequence or laws of physics. The audience will pretty much buy anything it sees on the screen, because the universe of Silent Film is on another plane of reality from the reality we experience outside of silent film.

That reality does not exist in sound film. The grounding of the performance in reality by the real-time speed of the camera and the synch-sound is what comedians lost in gag-making when sound came in. It was much deeper than “we had to tell jokes now” or that Chaplin had to find a voice for the little tramp.

In Silent Film, you had — and have — free reign to come up with absolutely anything you could imagine and put it on the screen. Especially if it was something you could only conceive of happening in a dream.

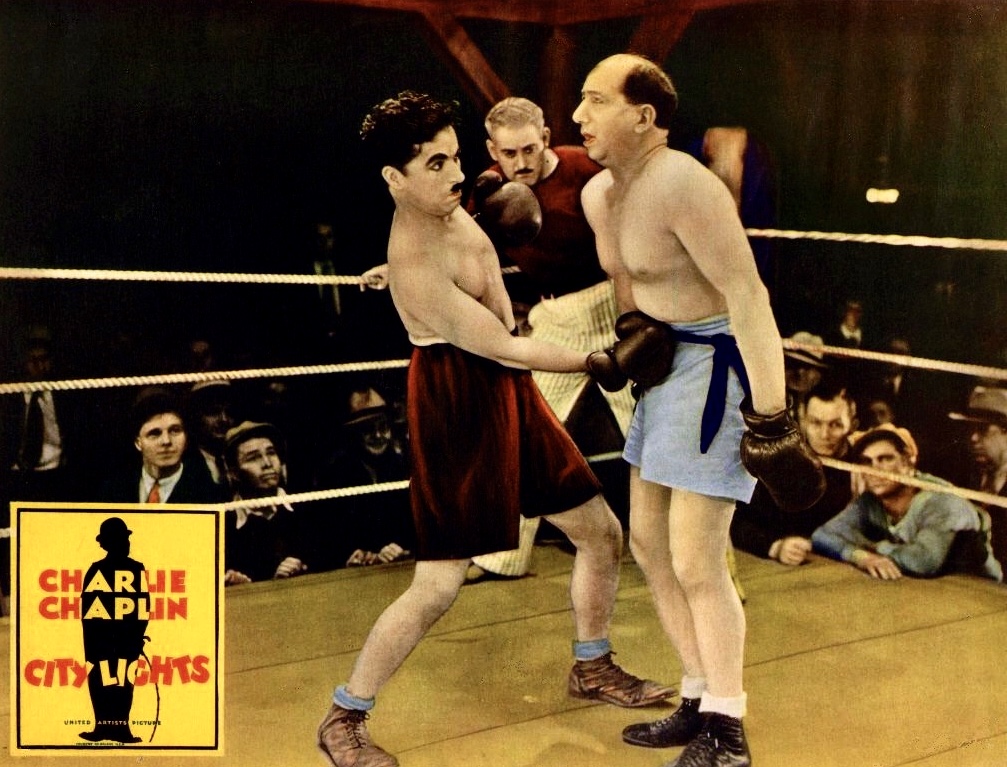

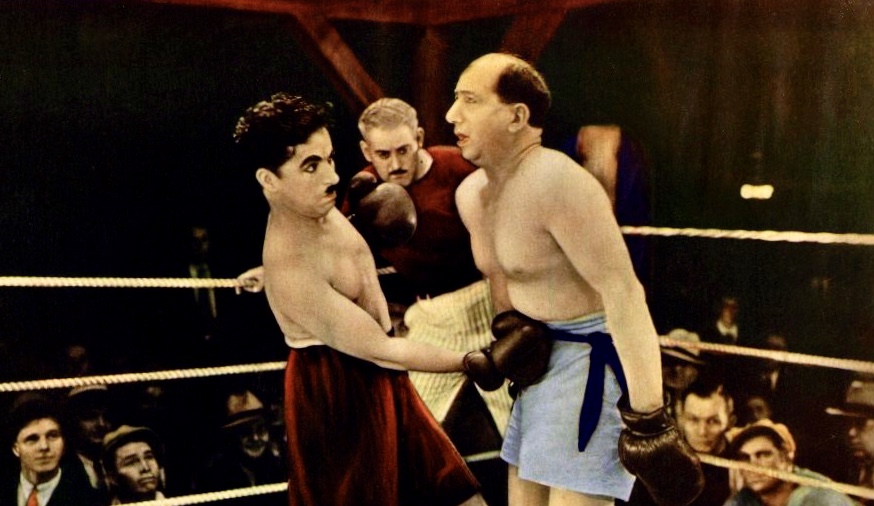

I encourage you to watch the video essay I made for the Criterion Collection called A Study in Undercranking for the Blu-ray of Chaplin’s The Kid, which is also on Criterion’s streaming channel. Also checking the video deconstructions of silent comedy sequences on my “silentfilmspeed” YouTube channel.

The first post in this series is here.

The previous post (#52) to this one is here.

The next post (#54) is here.

One of my favorite impossible gag is in Keaton’s “The Goat”, when Buster quickly pulls on the arrow of the elevator floor indicator (or whatever that thing is called) past the last floor #, and then we see the elevator go flying up through the roof of the building. That is a very funny, cartoonish gag that always makes me laugh.

Precisely! I show my students this short and Sherlock Jr. to show off precisely how far you can bend reality in silent film and silent film comedy.

A lot of similarities between Keaton’s silents and early Bugs Bunny. I can see that now!

Frank Tashlin did “impossible gags” in some of the live action films he directed, a carry over from his cartoon work

Yes…shows you why he was a good match to work with Jerry Lewis.

Is the acceptance of unreality, at least in part, because of the missing elements as you noted in another recent blog, so that the mind has to conceive of narrative with missing pieces, might it not open up other possibilities and freedoms? Or does it have more to do with the tradition of silent comedies roots in pantomime, magic lantern, vaudeville and it simple evolved that way? Great essay, thanks.

Eric, this is a great question, and I’m glad you mentioned this. Sometimes I’m too close to the material to realize I haven’t covered an aspect of it, and you’ve given me an idea for a follow-up post. Thanks!

and Steamboat Bill, “Jr.” where the wall falls around Keaton?

Hooray!!! It’s always a good day when Jerry gets a mention!