Sometimes the expositional sub-titles in Silent Film may have a little more personality or a persona to them. But not always consistently throughout the picture. This is not set up for us in any way, it merely happens.

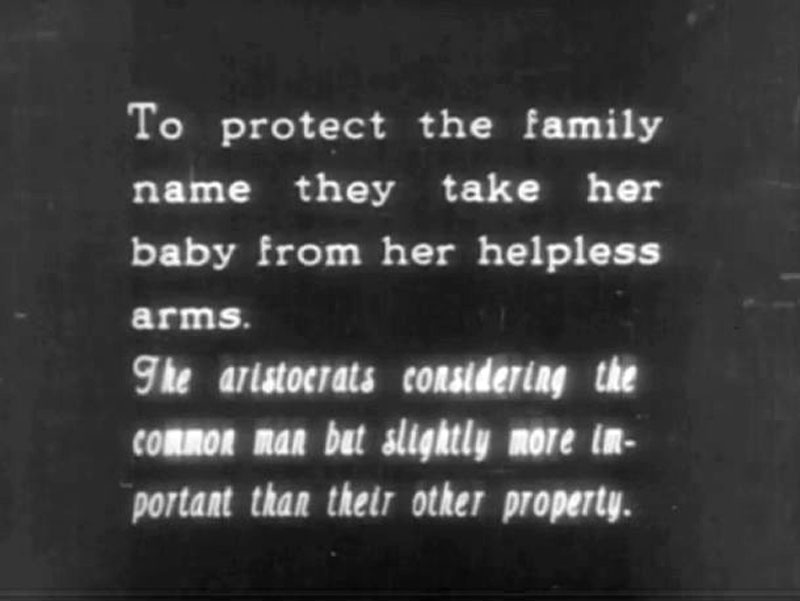

One somewhat prominent example is D.W. Griffith, in his features of the late ‘teens and early ‘twenties. A point is made about intolerance throughout the 1916 movie of the same name. Griffith does not identify himself as the speaker, but his presence is known enough that we know who it is. The film also has expository titles that do not have Mr. Griffith pointing out to us that people in society’s upper echelons have no empathy for the poor and the downtrodden. The same is true of Orphans of the Storm (1921). There are multi-sentenced title cards that let us know that time has passed, what has happened to Lillian and Dorothy Gish’s characters, etc. But there are other cards with similar word counts that speak of artistocrats’ “pussy-footing” behavior.

What’s unique about this kind of usage is that as viewers we accept it, and aren’t completely thrown by the fact that the director/auteur’s mindset has bled over into the narration, and we don’t wonder where it went in the next five or six of the film’s expository titles.

Chaplin does something similar, although with a much smaller word count. The Immigrant (1917) has titles that read, simply “Edna and her mother”, “Alone and hungry” or “‘He was ten cents short.'” However, when the boat of immigrants approaches Ellis Island, there is a title “Arrival in the land of liberty”. The immigrants gaze in awe at the Statue of Liberty and then, moments later, are roped off like cattle by ship officers. In Behind the Screen (1916) the title “The comedy department trying something new” is followed by a pie fight.

In these two cases, the point is made in the shot(s) after the title has appeared. The difference here is the point gets made in our heads. We assemble the title and the action.

There are title writers who definitely bring a little more personality to their text, usually in comedies. Many of Douglas Fairbanks’ pre-Zorro “coat-and-tie” films have a sense of whimsy and fun in their sub-titles, written by Anita Loos. The style neatly meets the fun Doug is clearly having outside of the titles. And you can tell the handiwork of H.M. “Beanie” Walker’s title writing, even if you’ve dipped in to a mid-20s short in the middle without knowing it’s a Roach-produced comedy.

There’s room within the form or format of expositional sub-titles in silent film for more than one perspective, and our human imagination will buy it, because we’re in the state of narrative flow that only exists in the experience of Silent Film.

The first post in this series is here.

The previous post (#21) to this one is here.

The next one (#23) is here.