Sometimes I see motion picture film exhibition referred to as “reel-to-reel”. I get why the term is used, as it conjures up the correct booth image better than “non-digital” does. I got to experience “classic” film projection at Capitolfest this past weekend that went one step further than just running 35mm prints.

The Capitol Theatre in Rome NY, like a mere handful of decades-old movie palaces still showing movies, has the capability to show film with carbon-arc projection. This involves a type of illumination that does not involve a lamp or bulb. It is literally an arc of light that bridges two rods made of carbon. Yes, kind of like the image you may have just thought of from old Frankenstein movies.

I realize this may not be news to everyone who reads my posts, but there were enough people I talked with at Capitolfest who did not know about this that I thought I’d (if you’ll pardon the pun) illuminate what carbon-arc is how it works to you in a post. Some of this is simplified and rudimentary, and there’s way, way more to it technologically than what I’m describing here for classic movie fans.

My initial reason for wanting to visit the projection booth to see this in action on Saturday was to take photos to show the students who take my silent film history class at Wesleyan. I’d like to thank to Phil Williams and Bob Hodge, the Capitol Theatre’s ace projectionists, for letting me visit the booth during a show, explaining the process to me, and letting me take and share these photos.

The projectors have two sections: the part where the film is threaded, and the lamp housing. The projectors, along with everything else in the booth, are on regular AC current. The carbon arc lamp runs on DC. As it was explained to me, it has to, as the way the arc is created is by positioning two carbon rods — one positive and one negative — slightly apart from one another, and this requires a DC current.

The inside of the lamp housing is about 2 feet long by 1 foot high and has a curved mirror reflector at the back to focus the light.

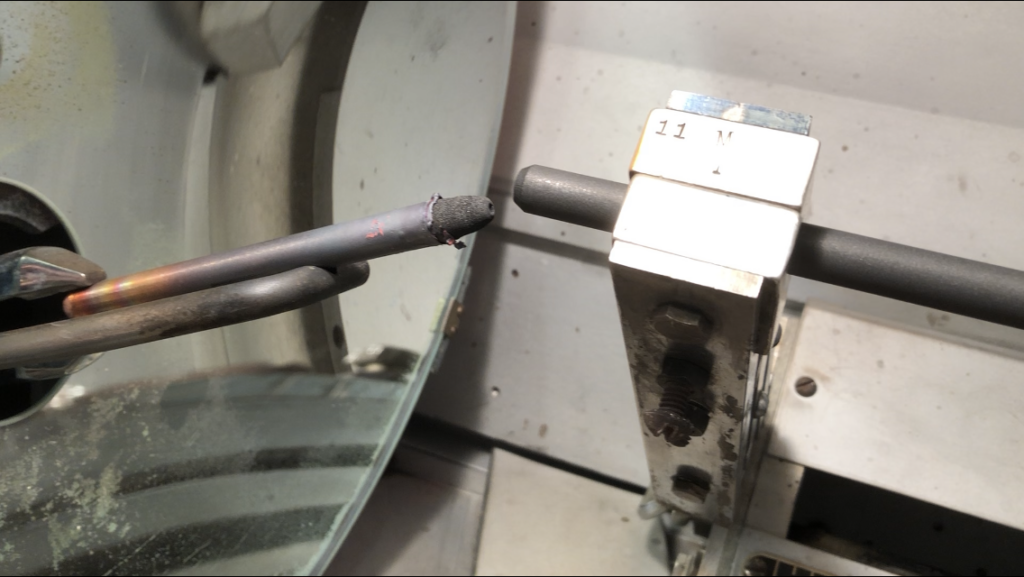

The two carbons are held in place by what are called jaws, which rotate slowly to maintain the distance between the two rods as they burn down.

The carbon rods used in the projectors at the Capitol last for three 2000’ reels of film. A full 2000’ reel of 35mm film is 22 minutes long.

At the back of the lamp housing is a device that uses water to cool the jaws which, as you can imagine, get quite hot.

When the carbon arc is switched on, it’s of course too bright to look at, but it does need to be monitored. There is a piece of glass like you’d have on a welding helmet on the side of the housing that you can look through.

There is also a small flat circular device on the outside — I didn’t get to notice if it’s opaque or frosted glass — which shows the illuminated arc, inverted.

This whole process is safe, regulated, insulated, etc, and was used in movie theater projection for decades. The color temperature, if you’re aware of it at all, is slightly different from the Xenon projector bulbs you’re used to seeing in film projection. It’s just a hair warmer, but there’s something else about the look of the films I saw onscreen at the Capitol during Capitolfest that I can’t really describe.

It has to be seen or really experienced to grasp.

If you’re a classic movie fan, if you have a chance to see 35mm film shown with carbon arc projection, absolutely go. You’ve got a slightly better chance of seeing carbon arc than you do of seeing nitrate film shown, and it’s just as special and “old school” of a classic movie-going experience.

It’s my understanding that carbon arcs produce a pure white light, while quartz or Xenon bulbs do not. This would explain why sometimes, when you see a changeover on a B&W film, the image suddenly seems to have a slightly green or brown tinge. It’s also why wires on older pictures (like Republic’s CAPTAIN MARVEL) are now visible, because they were calibrated to disappear in the light of carbon arcs, but not the tinted light of modern bulbs.

I have about 100 Carbon Arc rods 6mm dia that are marked GCE cinema

That’s amazing. There are some cinemas that still use carbon arc projection.

This really is so totally, utterly fascinating to me because at last I properly understand what those “things” (my word!) were at the beginning of the opening sequence of Bergman’s Persona. We see one of these carbon rods illuminating and then failing – is that right? I wondered what the technology was and even how real it was – so thanks for illuminating it for me to recycle your pun. Were they only used in the projection of 35mm prints?In Persona the print seems to accidentally self-destruct – is this because of the heat produced by the rods? Could such a malfunction occur? Please forgive my horrid ignorance. I know very little about all this.

Yes, as far as I know carbon-arc projection was only used with 35mm. Smaller gauges didn’t need that kind of brightness so an incandescent bulb was fine for 16mm and 8mm and 9.5mm. Amazing to think that this was the standard type of lamphouse to project nitrate for decades!

Carbon arc projectors were used for 16mm as well in larger venues.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/41002268@N03/4488290087

I was a projectionist for many years and have used both the RCA shown above and Bell & Howell carbon arc projectors.

Great information! Thanks for sharing this and for the links1

When I was in high school, the school auditorium had a 16 mm carbon arc projector in the projection room to show 16 mm educational films. I was involved in operating it. It used 6 mm diameter positive carbon rods operating at 30 amps DC. It had a lower color temperature of about 4500 Kelvin to be more compatible with 16 mm films processed to be shown with incandescent bulbs.

A little detail about the lamps at the Capitol. The Ashcraft lamps were installed new in Philharmonic Hall in Lincoln Center NYC in 1962 (the name changed to Avery Fisher Hall in 1976 and recently to David Geffen Hall). They were run twice a year for the New York Film Festival presentations from 1963 to 2000. While not in use, the lamps and projectors were covered with custom zippered canvas covers built by the Lincoln Center costume department for protection. When the lamps were replaced with Xenon in 2000, I removed and stored the lamps and rectifiers personally (I couldn’t bear to see them in a dumpster). A few years later, Bob Throop gave me a call asking about the lamps for the Capitol. I was happy to see them go to an good theatre (as long as I didn’t have to ship them ;-)) to allow these excellent specimens of carbon arc technology to live on being operated by a competent and caring crew. – Brad

I ve worked on towboats on the Mississippi river for a number of years, and have been on vessels that had carbon arc searchlights, most have gone to 1000 watt bulbs or zeon searchlights now.

An Ashcraft Super Cinex, I’m guessing, and IMHO, the finest carbon-arc lamp house ever made. Ran 35mm for many years and had these at my two primary employment venues, the Southroads Cinema and Admiral Twin (of “Outsiders” fame) in Tulsa with IATSE Local 513. First encountered it, paired with Simplex X-L’s, at the Beach Theater, in Virginia Beach, where I ran movies for IATSE Local 550. I know a lot of old Strong aficionados would put up a decent argument, but I cannot think of a negative point against the Ashcraft. Never, once, lost the light from one, and they were a breeze to retrim, strike and adjust; the latter being a rarity. It saddens me to think how these great US manufacturers, gradually and permanently, disappeared. Strong lasted up until a few years ago and only their spotlight division, I believe now privately owned, is all that’s left of the “old” equipment manufacturers. Sad. Running 35mm changeovers was a job that I loved to go to, and I am forever grateful I was able to work in the industry during this period of its evolution.Digital, while spectacular in its own ways, can never compare to running “real film.